Meet the World’s Longest-Running Queer Theater, Here in SF — or on Zoom

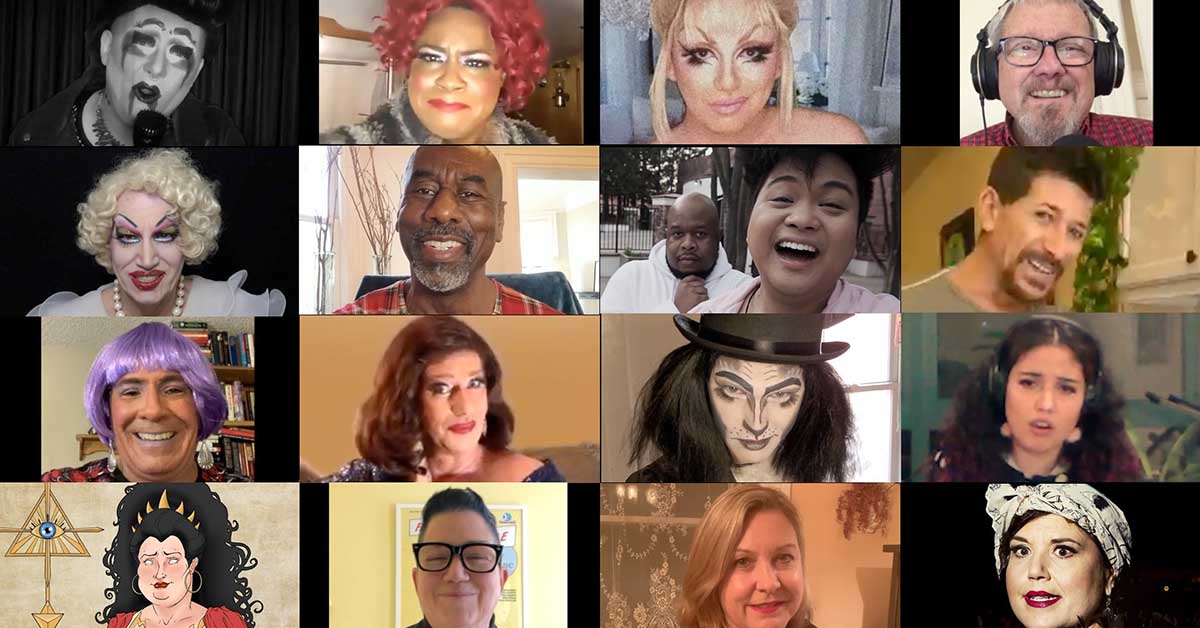

San Francisco’s Theatre Rhinoceros, founded in 1977, is the longest-running continuously producing LGBTQ theater in the world. Led by Executive and Artistic Director John Fisher, it was also one of the very first theaters to transition to digital performance when COVID-19 hit.

On Wednesday, March 11, 2020, the Bay Area began shutting down larger theaters. By Saturday, smaller companies like Theatre Rhinoceros were also halted — the same day that an encore run of Radical, a sold-out play written and directed by Fisher, was set to open. The show was allowed to go on… for one night only.

“I think it was literally the last public performance of a live piece of theater in San Francisco, and it was very scary,” Fisher told 94.1 KPFA. “The next day, Sunday, there was no theater in San Francisco, and then on Monday, there was shelter-in-place.”

Rather than pausing to regroup, The Rhino — as Theatre Rhinoceros is fondly known — forged ahead on a new path. Just days after shelter-in-place took effect, Fisher broadcast the first installment of his Essential Services Project: a series of solo plays written and performed by Fisher, presented over Zoom and Facebook Live every single week of the pandemic.

“Going into COVID-19, there was a lot of talk about essential services, and I took that to heart,” he explains of this major undertaking. Fisher notes the importance of the frontline workers that have come to be referred to as “essential” during the pandemic and continues: “I also feel that culture is essential and that, without culture, we kind of lose our footprint on history. With the loss of live performance, I think we’ve lost a certain access to the future because we’re no longer providing that unique moment of creation in time.”

With the support of an emergency COVID grant from Horizons, the company quickly adapted to circumstances by moving online and continuing to do what they do best: facilitating nourishing experiences for queer artists and audiences alike.

“I think it just was self-generating,” reflects Fisher. “It was a way to say, ‘We’re here, we’re queer, we’re not gonna lay down and disappear.’ And then it became self-generating because people actually enjoyed it.”

In addition to Fisher’s weekly solo shows, The Rhino presented a season of digital plays by a variety of artists, to great success. But of course, the transition didn’t come without its challenges: namely, the financial aspect of audience expectations.

“[Traditional theater is] indoors, it’s people packed together watching something, it’s just — that’s not gonna happen,” says Fisher. “And if people can’t do that, they don’t see the point in paying for it.”

“So we’re saying, ‘You know what, we want you to see this story. Come see this story for free,’” continues Fisher, before adding cheekily, “and some people make a donation afterwards!”

This decision to value accessibility over revenue reflects Fisher’s deeply held conviction in the importance of art during times of crisis — and the role of queer theater in particular.

“People say to me, ‘Why do you need queer theater? The big theaters are doing queer theater, and they’re doing queer theater on Broadway,’” remarks Fisher. “And I’m like, ‘Well, they’re doing a certain kind of queer theater.’ And also, they’re not doing it all the time.”

Grassroots queer theater companies like The Rhino, on the other hand, are of, by, and for their community. They stage bold, provocative works written by and representative of the full spectrum of identities and experiences — “both the ordinary and extraordinary aspects” — that comprise the LGBTQ community.

“When we tell a story, it’s about diversity, and about intersectionality, and about the breadth of queer life. It’s not just about one type of queer life which is digestible by the masses,” emphasizes Fisher. “Horizons is committed to organizations that are committed to queer life. It’s not just occasionally, or once a year, or once every summer — it’s consistent.”

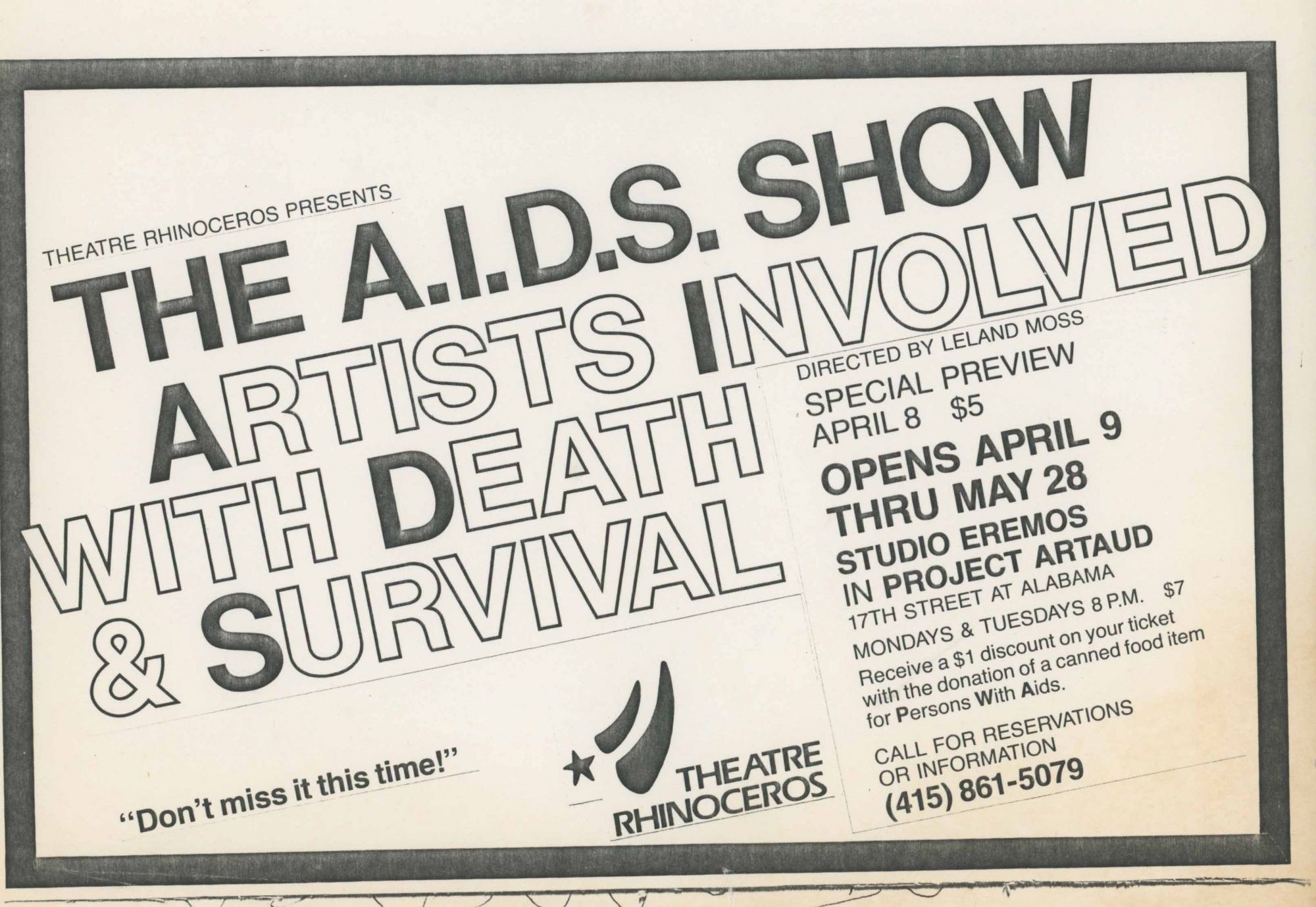

Poster for The AIDS Show: Artists Involved with Death and Survival

Catalyzed by the tragically early death from AIDS of Allan B. Estes, Jr. — The Rhino’s co-founder and first artistic director — The AIDS Show was the first major work by any theater company in the nation to deal with the AIDS epidemic, years before shows like Angels in America and Falsettos premiered. The play was co-authored by over a dozen San Francisco/Bay Area artists and garnered national recognition as groundbreaking work, soon becoming the subject of a 1986 PBS documentary adaptation of the same name.

“The theater has a history, long before my time, of changing gears, bouncing back,” comments Fisher, “and if you look at the stories told, they really track the course of gay life.”

After The AIDS Show ran for two years and toured the United States, The Rhino sharpened its focus on confronting racism within the gay community. Under the leadership of Kenneth R. Dixon, the first African American artistic director of a gay theater company, the theater staged a historic interracial production of Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band in 1989, as well as many shows by Black and Latinx artists. With support from Horizons dating back to 1990, The Rhino commissioned dozens of new works by emerging lesbian playwrights throughout the early 1990s, including funding specifically for lesbians of color.

Theatre Rhinoceros’ latest season echoes this long commitment to intersectionality, centering stories by and about queer and trans Black and Latinx people. Several draw on local or national LGBTQ history, which Fisher sees as an opportunity for education and engagement.

“We can do a play by Kheven LaGrone, who’s [written] a lot about African American queer life in West Oakland before gentrification,” says Fisher, referencing LaGrone’s recently premiered play, Pillow Talk. “I think that that is so interesting, to sit with an audience and watch the stories that he shows, because I don’t think that most people think of West Oakland as a place where drag queens lived, where trans people lived — and a place that they could live because it was affordable, and it was accepting.”

The Rhino’s 2020-21 season opener — Overlooked Latinas, written and performed by Tina D’Elia — also spotlights undertaught California history, exploring Latinx female movie stars who were displaced by Hollywood for their radicalism.

“Tina D’Elia’s work was a great archaeological, historical resuscitation. And funny!” exclaims Fisher. “That was the best part about it… It was a joyous comedy, and yet I felt like I learned a lot just by putting it on — and I think a lot of people did by watching it.”

Shows like Pillow Talk and Overlooked Latinas speak to the heart of what Theatre Rhinoceros strives to do and why the theater is crucial to the Bay Area’s queer culture.

“If I can give voice to people like Kheven and his archaeology of a lost urban community, then I think I’m really accomplishing something,” concludes Fisher. “I feel like [Theatre Rhinoceros’ work is] restoring a unique history to the queer community.”

From Theatre Rhinoceros’ first play staged in a SoMa leather bar in 1977 to today’s Zoom productions, the company has relentlessly championed an integral component of our movement: a revolutionary insistence on queer visibility.

Whether inspired by history or rooted firmly in the present day, The Rhino’s work exemplifies the rich contributions that long-standing, local LGBTQ institutions offer. Much like Horizons, Theatre Rhinoceros has been a pillar of the Bay Area LGBTQ community for decades and, no matter the challenges thrown its way, will remain so for decades to come.