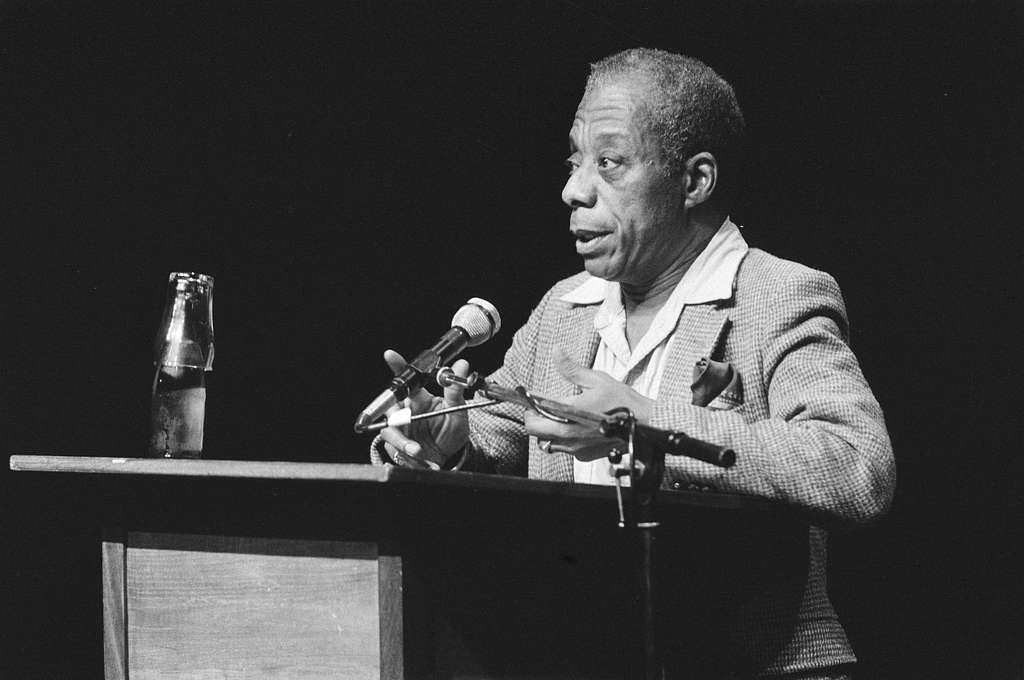

Remembering James Baldwin on his 100th Birthday

At the opening of his essay, “No Name in the Street,” published in 1972, James Baldwin tells of (as a young boy) hearing his mother say, “This is a good idea,” while she was incidentally holding a piece of black velvet in her hand. In his child’s mind an “idea” was inextricably linked with a piece of black velvet. James Baldwin’s ability to continually open his thoughts and his memories to us in this way is at the heart of the effectiveness of his words.

I spent three years re-reading Baldwin’s work in preparation for writing my play about him which was commissioned and produced by New Conservatory Theatre Center. I examined the principals which drove him as a writer and activist as well as absorbed the rhythm and tones that shaped his language. I came to understand what it meant that Baldwin had been a preacher. Not just in his Harlem childhood but his entire life. His ministry was not of the fire and brimstone variety but more personal with thoughtfully framed exhortations to look inside ourselves for truth and salvation.

His delivery was as distinct and effective as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or Nina Simone. Unlike the tedium that usually set young congregants to fidgeting, Baldwin knew the chords that kept our attention and vibrated inside of us. The cadence of his voice carried the words like waves relentlessly returning to the shore.

Baldwin was always examining and distilling ideas and information much of which was already known by Black thinkers and by our grandparents. His prose, although elegant and sometimes erudite, was never merely an intellectual exercise. His gift was finding the personal story, told with the right rhythm and chords that could exhort any of us (not just believers) to think and to act.

Much of what he recounted in the 1970s would alert us to what was to come. The essay, “No Name in the Street,” comes after the personal anguish Baldwin felt at the assassinations of Dr. King and Malcolm X as well as the relentless attacks by the FBI on Black activists in general and the Black Panther Party specifically. He wrote:

“…ignorance allied with power is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.”

Baldwin’s assessment of how this classic partnering of ignorance and power was wreaking havoc on Black and poor communities around the country was and is timely. More than fifty years later we face the same unholy alliance on a national level. While our mouths drop in disbelief at the embarrassing and ignorant statements made by our fellow citizens as well as by elected officials we should not be surprised. Baldwin warned us.

Each idea, every outrage, all the love he wrote about grew from his personal experiences and were shared as an aid for us to find the way toward our own insights and activism. Perhaps the young Baldwin was correct: his ideas and words might indeed be black velvet: soft, dense, elegant, carrying centuries of crucial history.